I'm staying with my parents for a couple of days before I leave, and on the plane here and then again yesterday afternoon I had time to read the second volume of Roy Foster's two-volume biography of W.B. Yeats. It came out in 2003, so I've taken my time getting around to it, but considering that volume one came out some ten years before that, and I didn't get around to reading it until last summer, I think I'm doing quite well on this one. I'm up to page 200, and here's what I've gleaned about W.B. Yeats: he was a very silly man. Remarkably so. I knew that he didn't get married until he was 52, because he spent all the first 52 years of his life yearning after first Maud Gonne and then her daughter, but unrequited

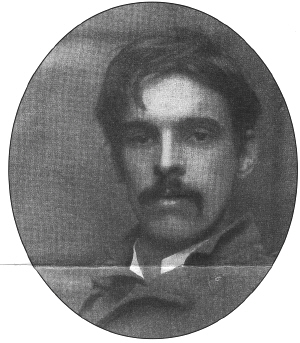

love is hardly a besetting silliness (and that young Yeats on the right looks as if he were made for unrequited love, after all). From reading the first volume of the bio I also knew that he had been involved with the Order of the Golden Dawn and with Theosophy, both reasons for eye-rolling, but in youth people get involved with all sorts of nonsense, so while that was worthy of a giggle it didn't inspire much more.

But I mean, really! It turns out it wasn't just foolish unrequited love (I mean, consider the work of loving someone unrequitedly for 30 years. Most of us would just give up around year 10), or silly pseudo-archaic names upon joining the Lodge of the Golden Dawn (or whatever it was), or joining the SPR, or saying that come Irish Independence evening dress for gentlemen should include saffron kilts. No-ho-ho! There is the credulous belief in his wife's obviously manipulative "automatic" writing; there is the attendance at seances, including one in which he was convinced that the medium had conjured up his father because said "conjurance" reportedly accurately that his (Yeats's) sister's neighbor's dog had died; there is the casting of horoscopes and believing them; there are the attempts to prove a correlation between physical beauty and spiritual superiority; later there is the support of fascism. I can't decide whether this is the result of nobody's ever telling him he was a fool, or whether even if they had told him he wouldn't have listened. It flummoxes me, though, that such nonsense could have been associated with such poetic gifts. Of course I know that a poet need not bear any resemblance to his personhood, that

the ability to write marvelous poetry has nothing to do with decency or good sense in everyday life (T.S. Eliot, anyone?), but in Yeats's case it's like watching a boat float despite the cairn of stones that slowly builds up inside it. Foolish psychic beliefs? Check. Willingness to believe in mysterious forces that run the world? Check. Addiction to societies that require "mystic rites" and special talismans and tokens of belonging? Check. Foolish beliefs about sex? Check. Pompous conviction of own superiority? Check. Said conviction leading to credulity? Check. You'd think his rowboat of ability would sink to the bottom, but instead you get "Sailing to Byzantium," and "Among Schoolchildren." And someone who ends up looking as much like an elder statesman as it's possible to look.

the ability to write marvelous poetry has nothing to do with decency or good sense in everyday life (T.S. Eliot, anyone?), but in Yeats's case it's like watching a boat float despite the cairn of stones that slowly builds up inside it. Foolish psychic beliefs? Check. Willingness to believe in mysterious forces that run the world? Check. Addiction to societies that require "mystic rites" and special talismans and tokens of belonging? Check. Foolish beliefs about sex? Check. Pompous conviction of own superiority? Check. Said conviction leading to credulity? Check. You'd think his rowboat of ability would sink to the bottom, but instead you get "Sailing to Byzantium," and "Among Schoolchildren." And someone who ends up looking as much like an elder statesman as it's possible to look.Ah, well, there's no accounting for gifts, I suppose. Or for foolishness. W.H. Auden said of Yeats, "You were silly like us," and while that could mean, "Just as we are silly, you were silly, too," it could also mean, "You were silly in the same ways we are." I would like to think that everyone in the human race has loved someone who didn't love them back, or believed some sort of nonsense, and I suppose in some way it is heartening to see genius (or whatever Yeats had) allied to humanity rather than to superiority. Interestingly, either reading of Auden's line suggests that at least part of the reason why one might like Yeats is precisely because of his silliness, not in spite of it. And I suppose that's true, just as one loves someone for their imperfections rather than their perfections. Without silliness or imperfection, the wall is sheer; with them, there are footholds.

No comments:

Post a Comment